In this post we’ll explore the different alternatives one has to log data from a microcontroller to some host machine. Be it for printf style debugging or for logging sensor data.

The Blue Pill

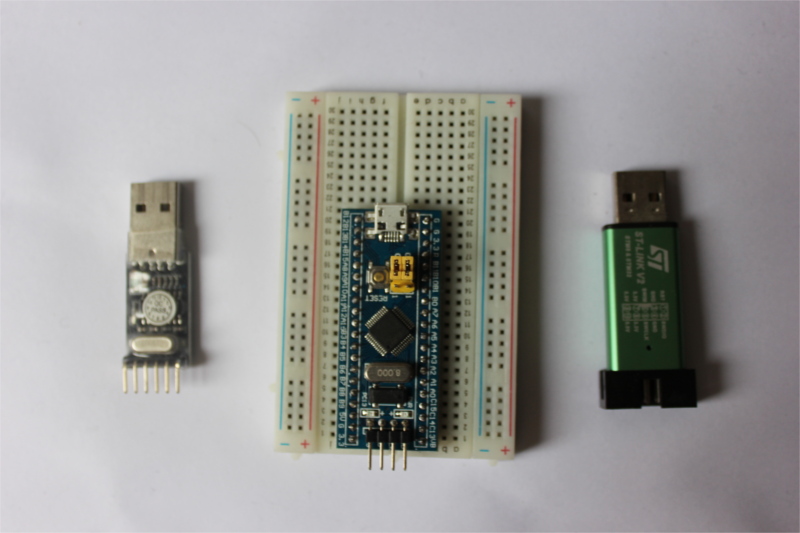

This time I’ll use a different development board: the Blue Pill.

On the center the Blue Pill development board. On the left side a UART to USB adapter based on the CH340G. On the right side an SWD programmer: a Chinese clone of the ST-LINK.

If so far you have been tagging along without getting your hands dirty then this a good starter kit. I bought these for around $5 1 2 3 with free shipping to Peru. I’m quite fond of this board mainly because of its form factor; it can fit in [lots] of interesting [places] :-).

These are the specifications of the Blue Pill:

-

STM32F103C8 microcontroller. 72 MHz, 64 KB (or 128 KB if you are lucky) of Flash memory, 20 KB of RAM, UART, I2C, SPI, ADC, PWM, timers, etc.

-

Pretty much all the pins of the microcontroller are exposed. Pinout diagram.

-

Micro USB port connected to the USB pins of the STM32F103.

-

32.768 KHz crystal (for the Real Time Clock).

-

8 MHz external crystal.

-

Power LED and one user LED

-

Reset button

-

SWD header

And that’s it. It’s a pretty bare bones development board.

Now on to the main topic.

Semihosting is very slow

In the first post I showed you a way to print messages to the console: the

hprintln! macro. This macro uses a technique called semihosting

and requires that the program runs under a debugger like GDB.

Let’s see how slow this macro actually is with this program:

fn t1(_task: Exti0, _prio: P1, _thr: T1) {

// read CYCCNT

hprintln!("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.");

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

(You can find the full source code of this program in the appendix. We’ll modify this program throughout this post).

We’ll use the timing method I showed you in the last blog post:

> tbreak semihosting::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x02df1c0c

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x02df1c16

> print 0x02df1c16 - 0x02df1c0c

$1 = 10

10 cycles sounds very fast but that number doesn’t reflect the real cost of using semihosting. Semihosting calls halt the processor so CYCCNT doesn’t increase during those calls. In real time each call takes much longer.

To measure the real time spent we’ll use a timer that doesn’t stop when the processor is halted. Most hardware timers have this property, unless they’ve been configured to do otherwise. We’ll use TIM1, a 16-bit timer, to measure the elapsed time:

fn init(ref prio: P0, thr: &TMax) {

let rcc = &RCC.access(prio, thr);

let tim1 = &TIM1.access(prio, thr);

// Configure TIM1 in continuous mode and to run at 100 KHz

rcc.apb2enr.modify(|_, w| unsafe { w.tim1en().bits(1) });

tim1.psc.write(|w| unsafe { w.psc().bits(79) });

tim1.arr.write(|w| unsafe { w.arr().bits(0xffff) });

tim1.cr1.write(|w| unsafe { w.opm().bits(0).cen().bits(1) });

}

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

let tim1 = TIM1.access(prio, thr);

let before = tim1.cnt.read().bits();

hprintln!("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog");

let after = tim1.cnt.read().bits();

let elapsed = after.wrapping_sub(before);

// Volatile magic to make LLVM not throw away the result of the measurement

unsafe {

ptr::write_volatile(0x2000_0000 as *mut _, elapsed);

}

rtfm::bkpt();

}

We’ll configure the TIM1 timer to run at 100 KHz. Since it’s a 16-bit timer this should let us measure times of up to half a second without having to worry about keeping track of times the counter wraps around.

> continue

> x 0x20000000

0x20000000: 0x000029f1

> print 0x00002974

$1 = 10737

The measurement says 10737 TIM1 clock cycles. At 100 KHz one cycle is 10 microseconds, so the total time spent is about 107 milliseconds. That’s an eternity in microcrontroller time! Unless you are debugging timing insensitive programs then you should not use semihosting for any kind of logging.

What other alternatives do we have?

Serial

I’ve used a serial interface in the previous posts but didn’t go into much detail about it back then so let’s talk about it in this post.

Pretty much all the microcontrollers out there come with a UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver / Transmitter) peripheral that can be used for asynchronous serial communication. The UART is highly configurable but probably the most used configuration is the 8N1 configuration: 1 start bit, 8 data bits and 1 stop bit per data frame; 8N1 is probably what most people mean when they just say serial interface.

The speed of the interface, referred to as baud rate, can go from tens of bits per second (bps) to millions of bit per second (Mbps). Both sides of the communication channel must agree on the baud rate beforehand as there’s no clock signal shared between them – this is why it’s called asynchronous communication. The UART supports independent transmission (TX) and reception (RX) between the two end points through two signals, one per wire. Because they are independent the TX and RX signal don’t need to be in lockstep.

The signals that come out of the UART peripheral can’t be directly connected to a laptop or smartphone as none of those two usually has a serial port (much less one that operates at the 3.3V). However, one can use an adapter to convert the UART signal into a more common protocol. Possibly the two most common UART adapters are UART to USB adapters and UART to Bluetooth (RFCOMM) adapters. Putting an adapter in between enables communication between a microcontroller and a laptop.

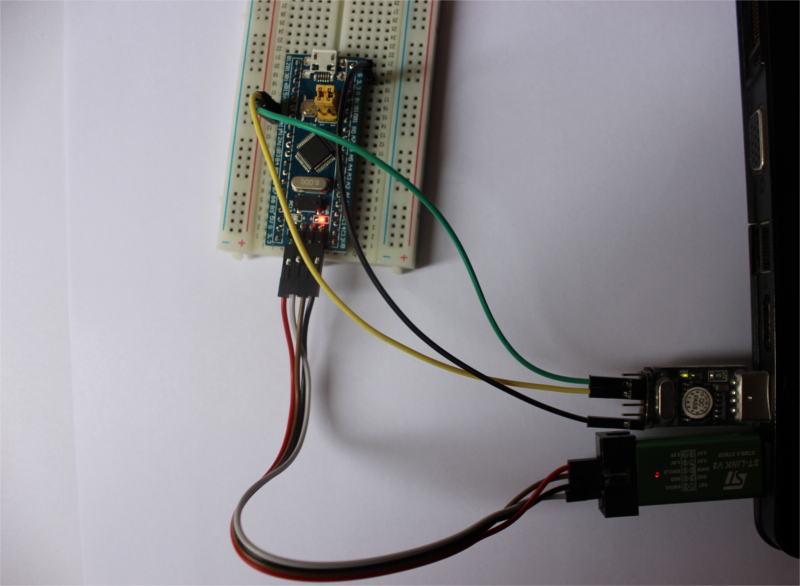

Below is shown the Blue Pill connected to my laptop using a UART to USB adapter, the one with the green and yellow wires.

We are looking for a fast way to log data so how fast can a serial interface go? It depends on the hardware. On the STM32F103 the baud rate can reach one sixteenth of the core clock (HCLK) frequency. HCLK defaults to 8 MHz on the STM32F103; that gives you a baud rate of 500 Kbps. The maximum HCLK frequency on the STM32F103 is 72 MHz; that would result in a baud rate of 6 Mbps. However, that’s not the only variable; you need take into account the adapter as well. The adapter I’ve shown above supports a maximum baud rate of 2 Mbps.

Let’s now do some measurements:

const BAUD_RATE: u32 = 500_000;

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// read CYCCNT

let usart1 = USART1.access(prio, thr);

let serial = Serial(&usart1);

for byte in b"The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog\n".iter() {

// `write` returns an error if the byte couldn't be sent due to the

// hardware being busy. This loop retries the write until it succeeds.

while serial.write(*byte).is_err() {}

}

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

We’ll transmit the same message as in the previous measurement.

> tbreak serial::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0028b969

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0028d3d4

> print 0x0028d3d4 - 0x0028b969

$1 = 6763

6763 cycles at 125 nanoseconds per cycle is 795 microseconds. That’s much better

than semihosting, at least two orders of magnitude better. Translating that to

bytes per second would be 44 B / 795 μs = 55 KB/s.

Can we do better? Yes, there’s a faster peripheral specifically designed for logging and tracing: the ITM (Instrumentation Trace Macrocell). Let’s try it.

ITM

Unlike the UART peripheral, which although ubiquitous varies per device, the ITM is a core peripheral and works the same – it has the same set of registers – on all the microcontrollers that have it (Cortex-M3+). Like the UART the ITM exposes an asynchronous serial interface but only allows one way transmission through the SWO pin (the PB3 pin on the STM32F103).

Some SWD programmers support reading the SWO pin. In that case the SWO pin can be connected to the SWD programmer and have the programmer take care of receiving the data. Some boards which have on-board programmers, like the STM32F3DISCOVERY (shown below), even come with the SWO pin already connected to the programmer so ITM will work by just connecting a USB cable to the board.

The ITM needs to be configured before you can use it but if you are using

OpenOCD then using the tpiu command from OpenCD will perform all the required

configuration. You can put that command in the .gdbinit file to have it run on

every GDB session.

$ cat .gdbinit

(..)

monitor tpiu config internal itm.fifo uart off 8000000

(..)

(This command is included, but commented out, in the .gdbinit file that ships with recent versions of the cortex-m-quickstart template.)

The above command will configure OpenOCD to capture the SWO output and write it

to the itm.fifo file (the internal itm.fifo part). The command will also

configure the ITM to use NRZ 4 encoding (the uart part). The final

argument, 8000000 in this case, must match the TRACECLKIN clock, which is

usually the same as the core clock frequency (HCLK). One can pass an extra

argument to the tpiu command that will set the frequency of the SWO pin. If

that argument is omitted OpenOCD will select the frequency of the SWO pin

automatically and try to use the highest frequency possible. In the case of the

STM32F103 OpenOCD will pick an SWO frequency of 2 MHz.

How do we receive the ITM message? Let’s find out with the following program:

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// read CYCCNT

let itm = ITM.access(prio, thr);

// This sends the string over the ITM stimulus port 0

iprintln!(&itm.stim[0], "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog");

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

If you run this program you’ll notice that an itm.fifo file will be created in

the same directory where you called the openocd command. Let’s check the

contents of that file:

$ cat itm.fifo

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

The message is there but is that all there is?

$ stat --printf=%s itm.fifo

55

$ python -c 'print(len("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog\n"))'

44

The file appears to have 11 extra bytes in there. This is actually expected: the ITM works with frames, and each frame has a 1-byte header. The header contains the size of the frame which can be 1, 2 or 4 bytes in size.

These headers are easier to spot if you print the contents of the file in hexadecimal format:

$ xxd -p itm.fifo

03546865200371756963036b206272036f776e2003666f7820036a756d70

0373206f760365722074036865206c03617a792003646f670a

There’s a bunch of 0x03 values in there; those are the headers of the frames.

After each header comes the payload of the frame, which is 4 bytes for every

frame in the previous case.

In this case the header didn’t cause problem when printing the contents of the

file, but this may not always be the case. It’s better to parse the frames and

only extract the payloads. That’s why the itmdump tool was created.

itmdump takes a path as its only argument; itmdump will create a named pipe

at that path. itmdump must be called before the GDB session begins. Once the

GDB session begins OpenOCD will start writing to the named pipe and itmdump

will parse the frames that come from the pipe and print the payloads to stdout:

$ cargo install itm --vers 0.1.1

$ itmdump itm.fifo | tee clean

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

$ stat --printf=%s clean

44

Now let’s time the ITM operation:

> tbreak itm::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x007b3dd2

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x007b4367

> print 0x007b4367 - 0x007b3dd2

$1 = 1429

1429 cycles at 125 nanoseconds per cycle is about 178 microseconds. 44 bytes in 178 microseconds is 246 KB/s.

The ITM version takes less that one fourth of the time the UART version took. This makes sense as the ITM stimulus ports are working at 2 Mbps, which is four times the UART speed.

Aligned buffers

Not only is the ITM wire speed is higher than the UART wire speed but the ITM also has a hardware FIFO buffer so the processor doesn’t have to wait until the data has been transmitted; it can push data into the buffer without waiting at least while the buffer is not full.

Also because the size of ITM frames can be 1, 2 or 4 bytes, for example, a 16 byte buffer can be transmitted in 4 32-bit frames whereas with the UART 16 8-bit frames would be required. This results in less register writes which means less processor work.

These two features don’t affect data throughput, but they reduce blocking /

waiting time. For maximum effect, though, the buffer to transmit must be 4 byte

aligned. The cortex-m crate provides a write_aligned function optimized

to send 4 byte aligned buffers and a general write_all function to send

buffers with unknown alignment at compile time.

Let’s compare those two functions:

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// Buffer with unknown alignment

static MSG: [u8; 7] = *b"Hello!\n";

// read CYCCNT

let itm = &ITM.access(prio, thr);

itm::write_all(&itm.stim[0], &MSG);

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

> tbreak unaligned::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0088e5b1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0088e5ed

> print 0x0088e5ed - 0x0088e5b1

$2 = 60

60 cycles for the buffer with unknown alignment.

// version = "0.1.1"

extern crate aligned;

use aligned::Aligned;

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// Buffer aligned to a 4 byte boundary

// The first type parameter specifies the alignment. `u32` equals 4 byte

// aligment, `u16` equals 2 byte alignment, and so on.

// The second type parameter is the type of the array

static MSG: Aligned<u32, [u8; 7]> = Aligned(*b"Hello!\n");

// read CYCCNT

let itm = &ITM.access(prio, thr);

itm::write_aligned(&itm.stim[0], &MSG);

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

> tbreak aligned::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0095a1f9

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0095a21a

> print 0x0095a21a - 0x0095a1f9

$2 = 33

33 cycles for the 4 byte aligned buffer. About half the time of the unaligned version!

If you look at the disassembly of this second version:

080006d6 <itm::main::INTERRUPTS::t1>:

80006d6: f04f 4060 mov.w r0, #3758096384 ; 0xe0000000

80006da: 6801 ldr r1, [r0, #0]

80006dc: 2901 cmp r1, #1

80006de: d1fc bne.n 80006da <itm::main::INTERRUPTS::t1+0x4>

80006e0: f246 5148 movw r1, #25928 ; 0x6548

80006e4: f04f 4060 mov.w r0, #3758096384 ; 0xe0000000

80006e8: f6c6 416c movt r1, #27756 ; 0x6c6c

80006ec: 6001 str r1, [r0, #0] ; 32 bit write

80006ee: 6801 ldr r1, [r0, #0]

80006f0: 2901 cmp r1, #1

80006f2: d1fc bne.n 80006ee <itm::main::INTERRUPTS::t1+0x18>

80006f4: f04f 4060 mov.w r0, #3758096384 ; 0xe0000000

80006f8: f242 116f movw r1, #8559 ; 0x216f

80006fc: 8001 strh r1, [r0, #0] ; 16 bit write

80006fe: 6801 ldr r1, [r0, #0]

8000700: 2901 cmp r1, #1

8000702: d1fc bne.n 80006fe <itm::main::INTERRUPTS::t1+0x28>

8000704: f04f 4060 mov.w r0, #3758096384 ; 0xe0000000

8000708: 210a movs r1, #10

800070a: 7001 strb r1, [r0, #0] ; 8 bit write

800070c: be00 bkpt 0x0000

800070e: 4770 bx lr

You can see that sending the 7 byte buffer translates to one 32 bit write, one 16 bit write and one 8 bit write to the ITM register. There are no loops; the operation has been unrolled by LLVM.

Standalone SWO

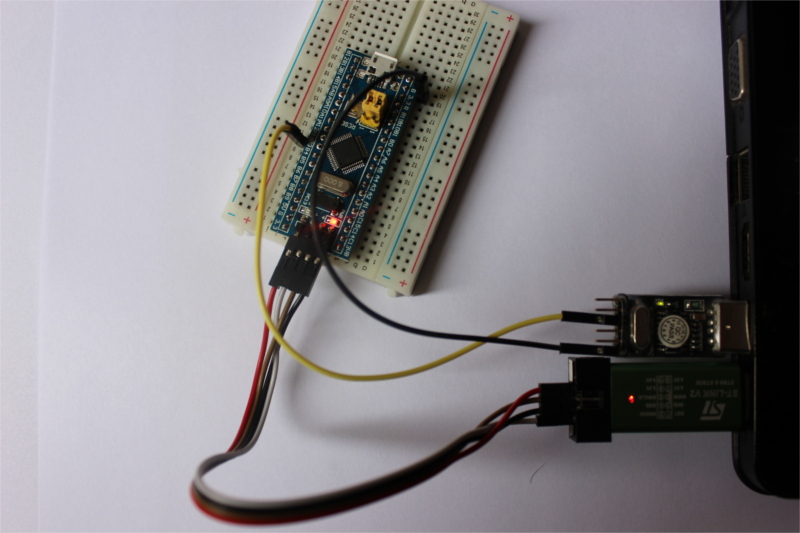

AFAIS most SWD programmers don’t support reading the SWO pin. For instance the ST-LINK I’m using doesn’t. However, you can still make use the SWO pin, and of the ITM, if you connect the SWO pin to a UART to USB adapter or similar. The ITM can be configured to output a NRZ signal, which is what we have been doing so far, and this signal is compatible with UART adapters.

Below is shown the SWO pin of the Blue Pill, the PB3 pin, connected to a UART adapter.

To use this different configuration the tpiu command needs to be changed:

$ cat .gdbinit

(..)

monitor tpiu config external uart off 8000000 2000000

(..)

external means “don’t capture SWO output into a file”, as the SWO pin may not

be connected. The final argument 2000000, which is now mandatory, indicates

the SWO frequency.

With those changes you can directly read, for example, the /dev/ttyUSB0 file

as if it were the itm.fifo file.

ITM vs Serial

Or why you should be using the ITM:

The advantages:

-

ITM’s transmission speed is faster than Serial’s. 2 Mbps vs 500 Kbps when the core clock frequency is 8 MHz, at least on the STM32F103.

-

ITM doesn’t need an extra connection or extra hardware but only if a SWD programmer is already connected to the device and the SWD programmer supports reading the SWO pin.

-

ITM supports all sort of other functions like sampling the Program Counter and tracking memory accesses.

Neither an advantage or a disadvantage:

-

If the SWD programmer doesn’t support reading the SWO pin then you need a UART adapter and one extra connection. This is also the case for Serial so neither is at a disadvantage here.

-

Both can be used without having the microcontroller connected to a SWD programmer. So they can be used in both development mode and in production.

The disadvantages:

-

ITM doesn’t work with the DMA (Direct Memory Access) peripheral.

-

ITM doesn’t support receiving data from the host whereas Serial does.

-

Cortex-M0 and Cortex-M0+ microcontrollers don’t seem to have ITM hardware, AFAIS.

Formatting is slow

Another thing you will probably want to do is format numbers into strings for human consumption rather than transmitting predefined strings. Let’s explore our options:

The baseline

For comparison we’ll measure the time it takes to format and print two i16

integers using the format string "{}, {}\n".

To get a better idea of how much time is spent transmitting the formatted string

and how much time is spent doing the formatting itself let’s first measure the

operation of sending the string "-32768, 32767\n", which is the largest string

that the formatting operation can produce.

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// read CYCCNT

let itm = &ITM.access(prio, thr);

iprintln!(&itm.stim[0], "-32768, 32767");

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

> tbreak baseline::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x000da167

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x000da1b0

> print 0x000da1b0 - 0x000da167

$1 = 73

73 clock cycles spent transmitting 14 bytes. Let’s also keep an eye on the size of the program.

$ arm-none-eabi-size baseline

text data bss dec hex filename

1356 0 0 1356 54c baseline

$ arm-none-eabi-size -A baseline

baseline :

section size addr

.vector_table 304 134217728

.text 1038 134218752

.rodata 14 134219792

1038 bytes of instructions (.text) and 14 bytes of constants / strings

(.rodata).

core::fmt

You first choice for formatting is probably going to be the core::fmt

machinery provided by the standard library. Let’s see how it fares.

static mut R1: i16 = -32_768;

static mut R2: i16 = 32_767;

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// read CYCCNT

// Volatile magic to prevent LLVM from inlining the values of R1 and R2 into

// this function

let r1 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R1) };

let r2 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R2) };

let itm = &ITM.access(prio, thr);

// This macro uses the core::fmt::Write trait

iprintln!(&itm.stim[0], "{}, {}", r1, r2);

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

> break format::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0167b40d

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0167b745

> print 0x0167b745 - 0x0167b40d

$1 = 824

824 cycles compared to the baseline of 137 cycles is 824 / 73 = 1128.77%, or

almost eleven times the baseline number.

Program size wise:

$ arm-none-eabi-size -A format

text data bss dec hex filename

4114 4 0 4118 1016 format

$ arm-none-eabi-size -A format

format :

section size addr

.vector_table 304 134217728

.text 3558 134218752

.rodata 252 134222312

.data 4 536870912

Compared to the baseline program the .text section increased by 2520 bytes,

and the .rodata section increased by 238 bytes.

numtoa

Another option is the numtoa crate. This crate provides an API for

formatting numbers into byte buffers ([u8]). We can use this crate to format

each number independently and then piece them together into a larger buffer.

Once that’s done we can transmit the whole thing.

// version = "0.0.7"

extern crate numtoa;

use numtoa::NumToA;

static mut R1: i16 = -32_768;

static mut R2: i16 = 32_767;

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// read CYCCNT

// Volatile magic to prevent LLVM from inlining the values of R1 and R2 into

// this function

let r1 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R1) };

let r2 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R2) };

let itm = &ITM.access(prio, thr);

let mut buffer = [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, b'\n'];

let n = buffer.len();

// format the first number

let start = r2.numtoa(10, &mut buffer[..n - 1]);

// add the comma

buffer[start - 2..start].copy_from_slice(b", ");

// format the second number

let start = r1.numtoa(10, &mut buffer[..start - 2]);

// send the whole buffer

itm::write_all(&itm.stim[0], &buffer[start..]);

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

Needless to say formatting the numbers manually is nowhere as ergonomic as using

the iprintln! macro.

> break numtoa::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x01503027

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x01503116

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x01503163

> # Total

> print 0x01503163 - 0x01503027

$1 = 316

> # Formatting

> print 0x01503116 - 0x01503027

$2 = 239

> # Sending the buffer

> print 0x01503163 - 0x01503116

$3 = 77

314 cycles is less than half the core::fmt number. Nice! 77 cycles, which is

the time spent sending the buffer, is pretty close to the baseline number. The

difference, 239 cycles, is the time spent doing the formatting itself.

Program size wise:

$ arm-none-eabi-size numtoa

text data bss dec hex filename

2318 4 0 2322 912 numtoa

$ arm-none-eabi-size -A numtoa

section size addr

.vector_table 304 134217728

.text 1814 134218752

.rodata 200 134220568

.data 4 536870912

Compared to the baseline program the .text section increased by 776 bytes, and

the .rodata section increased by 186 bytes. So numtoa saves around 1800

bytes of Flash memory compared to the core::fmt version.

fast_fmt

A new challenger to core::fmt popped up this week. It addresses one of the

main reasons of the core::fmt bloat: it doesn’t use trait objects in its

implementation; this improves inlining and results in smaller and faster code.

Let’s give it a try.

// git = "https://github.com/japaric/fast_fmt",

// branch = "do-not-delete-int-formatting"

#[macro_use]

extern crate fast_fmt;

use fast_fmt::Write;

struct Port<'a>(&'a Stim);

impl<'a> Write for Port<'a> {

type Error = !;

// ...

}

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// read CYCCNT

// Volatile magic to prevent LLVM from inlining the values of R1 and R2 into

// this function

let r1 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R1) };

let r2 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R2) };

let itm = &ITM.access(prio, thr);

// Equivalent to "{r1}, {r2}\n"

fwrite!(&mut Port(&itm.stim[0]), r1, ", ", r2, "\n");

rtfm::bkpt(); // read CYCCNT

}

This program requires a bit more of boilerplate because the ITM structs in the

cortex-m crate don’t implement the fast_fmt::Write trait so a newtype is

required to implement the Write trait. The fwrite! macro provides ergonomic

formatting

> break fwrite::main::INTERRUPTS::t1

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x01988932

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x01988a98

> print 0x01988a98 - 0x01988932

$1 = 358

358 cycles is close to the 314 cycles of the numtoa version, and it still is

much better than the core::fmt version. It’s reasonable to lose some

performance in exchange for improved ergonomics.

Let’s check the program size:

$ arm-none-eabi-size fwrite

text data bss dec hex filename

2605 4 0 2609 a31 fwrite

$ arm-none-eabi-size -A fwrite

fwrite :

section size addr

.vector_table 304 134217728

.text 2098 134218752

.rodata 203 134220852

.data 4 536870912

Compared to the baseline program the .text section increased by 1060 bytes,

and the .rodata section increased by 189 bytes. This uses around 300 more

bytes than the numtoa version but it’s still far from the bloat of core::fmt:

around 1500 bytes smaller.

Strings are slow

Sometimes you have to log data at a much faster rate. For example, if you are measuring the performance of a PID controller you may want to log the state of the system and the controller at 1 KHz or 10 KHz or even faster. In those cases logging data using strings is too onerous; you have no choice but to log data in binary format.

byteorder

byteorder is what I use for binary serialization these days. Let’s port our

running program about the 2 i16 integers to byteorder and measure:

static mut R1: i16 = -32_768;

static mut R2: i16 = 32_767;

fn t1(_task: Exti0, ref prio: P1, ref thr: T1) {

// Volatile magic to prevent LLVM from inlining the values of R1 and R2 into

// this function

let r1 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R1) };

let r2 = unsafe { ptr::read_volatile(&R2) };

// read CYCCNT

rtfm::bkpt();

let itm = &ITM.access(prio, thr);

// 4 byte aligned buffer

let mut buffer = Aligned([0; 4]);

// binary serialization

LittleEndian::write_i16(&mut buffer.array[..2], r1);

LittleEndian::write_i16(&mut buffer.array[2..4], r2);

// send the buffer through the ITM port 0

itm::write_aligned(&itm.stim[0], &buffer);

// read CYCCNT

rtfm::bkpt();

}

The annoying part is having to manually encode the data into the buffer but it’s actually not as bad as manually formatting them as strings. Let’s time this:

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x00000023

> continue

> x 0xe0001004 # read CYCCNT

0xe0001004: 0x0000002d

> print 0x0000002d - 0x00000023

$1 = 10

10 cycles! That’s about 30 times faster than the numtoa version we timed before. Here’s the disassembly of the program:

080006d6 <itm::main::INTERRUPTS::t1>:

80006d6: f240 0100 movw r1, #0

80006da: f04f 4260 mov.w r2, #3758096384 ; 0xe0000000

80006de: f2c2 0100 movt r1, #8192 ; 0x2000

80006e2: 8808 ldrh r0, [r1, #0]

80006e4: 8849 ldrh r1, [r1, #2]

80006e6: be00 bkpt 0x0000

80006e8: 6813 ldr r3, [r2, #0]

80006ea: 2b01 cmp r3, #1

80006ec: d1fc bne.n 80006e8 <itm::main::INTERRUPTS::t1+0x12>

80006ee: ea40 4001 orr.w r0, r0, r1, lsl #16

80006f2: f04f 4160 mov.w r1, #3758096384 ; 0xe0000000

80006f6: 6008 str r0, [r1, #0] ; 32 bit write

80006f8: be00 bkpt 0x0000

80006fa: 4770 bx lr

Only a single 32 bit write to the ITM register. The code doesn’t even place the buffer on the stack; it only makes uses of registers.

Unlike with strings you can’t directly visualize this binary output in a

serial terminal like minicom. Instead you’ll have to write some program to

decode the binary data and then print it or process it some other way before

presenting it. So this approach involves extra work on the host side.

… Unless you are good / fast at reading numbers in hexadecimal format. If that

the case then you can just use xxd :-)

$ xxd -p /dev/ttyUSB0

030080ff7f

Some of you may be wondering why I’m not using a proper serialization framework

like serde or bincode. The main reason is that I haven’t found one that

fits my need. I need serialization that doesn’t involve dynamic allocation,

and that doesn’t return a Result if the operation can’t fail.

About the second requirement: In interactive std programs you can just bubble

up the errors and report them as messages to the users. You can’t always do

that on a microcontroller. In some cases errors have to be dealt with very

locally, within the function where they occurred. Thus it’s better if you have

to dealt with less Results in your program.

So my ideal serialization framework would be just some #[derive] stuff on top

of byteorder. Something like this:

// This derive attribute

#[derive(BinarySerialization)]

struct Acceleration {

x: i16,

y: i16,

z: i16,

}

// expands into to this

impl Acceleration {

// Neither operation can fail

fn deserialize(buffer: &[u8; 6]) -> Self { .. }

fn serialize(&self, buffer: &mut [u8; 6]) { .. }

}

With perhaps some option to pick the endianness either at the #[derive] or at

every function call. This is what I write manually today.

Conclusions

-

Never, ever use semihosting to log data. Unless you can afford delays in the order of tens of milliseconds in your application.

-

If you can, use the ITM instead of the UART. The former has a faster transmission speed and uses less CPU time.

-

core::fmtis bloated. Luckily there are alternatives for formatting in the no-std ecosystem likefast_fmtandnumtoa. -

For the ultimate logging speed use binary serialization instead of formatting to strings. Until I see something better I recommend using

byteorderfor this purpose.

Thank you patrons! ❤️

I want to wholeheartedly thank Iban Eguia, Aaron Turon, Geoff Cant, Harrison Chin, Brandon Edens, whitequark, J. Ryan Stinnett, James Munns and 20 more people for supporting my work on Patreon.

Let’s discuss on reddit. How do you do data logging on embedded systems?

Appendix

#![feature(const_fn)]

#![feature(used)]

#![no_std]

// version = "0.2.9"

#[macro_use]

extern crate cortex_m;

// version = "0.2.3"

extern crate cortex_m_rt;

// version = "0.1.0"

#[macro_use]

extern crate cortex_m_rtfm as rtfm;

// git = "https://github.com/japaric/blue-pill",

// rev = "9cb1629b771e63fee85717b23f59b7c0dbd08014"

extern crate blue_pill;

use blue_pill::stm32f103xx;

use rtfm::{P0, P1, T0, T1, TMax};

use stm32f103xx::interrupt::Exti0;

fn init(_prio: P0, _thr: &TMax) {}

fn idle(_prio: P0, _thr: T0) -> ! {

rtfm::request(t1);

// Sleep

loop {

rtfm::wfi();

}

}

tasks!(stm32f103xx, {

t1: Task {

interrupt: Exti0,

priority: P1,

enabled: true,

},

});

fn t1(_task: Exti0, _prio: P1, _thr: T1) {

rtfm::bkpt();

hprintln!("The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.");

rtfm::bkpt();

}